Evan and Alex have been dating for a year and just moved in together. One night, Evan goes out with his friends. Alex sends him several text messages which are left unanswered. Alex is unable to fall asleep. His thoughts are racing: "I'm sure he's having more fun without me. I'm afraid he doesn’t love me anymore and will leave me.” Later, Evan realizes that he has several missed messages from Alex. Irritated, he decides not to answer them. When Evan gets home, Alex is angry and asks him: "Why didn't you answer me? Evan sighs: - You know I was busy. I’m home, should we go to bed now? Alex adds: - How do you expect me to go to bed in this state? You never see the problem, and I always feel like I'm asking too much of you. Evan is emotionally closed off. Wanting to avoid conflict, he says: - It's not that bad and I'm tired, this is not the time." Anyway, it is difficult for Evan to manage and express his emotions. Alex blames him for always putting off talking things through and never understanding him. So, they fall asleep angry.

What is romantic attachment?

As introduced in the blog article on Romantic Attachment 101, attachment is a basic need that develops through interactions with parental figures. They are the primary attachment figures during childhood. Depending on their presence and responses to the child's needs, the child integrates images of self and others that will later guide their relationships with loved ones (e.g., friends, romantic partners*)1,2,3,4,5. In adulthood, romantic partners become the attachment figures, which refers to romantic attachment6.

What are the dimensions of romantic attachment?

Romantic attachment has two dimensions7. First, anxious attachment refers to a negative view of oneself, a fear of abandonment or rejection, and a need for reassurance from partners. If this sounds familiar to you, you may have thoughts such as: "No one loves me," "If this person really knew me, they would leave me "7. This may present itself in your interactions with your partners. Such as, being acutely aware about their interest in you and their commitment to your intimate relationship8.

Second, avoidant attachment is characterized by a negative view of others, a strong need for independence, and discomfort with being vulnerable and intimate with partners emotionally, physically, and sexually. If this sounds like your experience, you may feel the need to protect yourself from others by saying to yourself: "I can't count on anyone", "I'm better off alone”7. In interactions with your partners, when you feel vulnerable, you may tend to feel a strong need to distance yourself and put your emotions aside8.

These two dimensions should be seen as two relatively stable axes over time, which can fluctuate according to your experiences8. You don't have to be at either extreme for these to reflect your experience. For example, you might feel generally confident in your intimate relationships but at times feel more vulnerable and alone without constantly fearing that the other person will leave you. You may also slightly distrust others without necessarily feeling that you can't rely on them.

What are the possible romantic attachment styles?

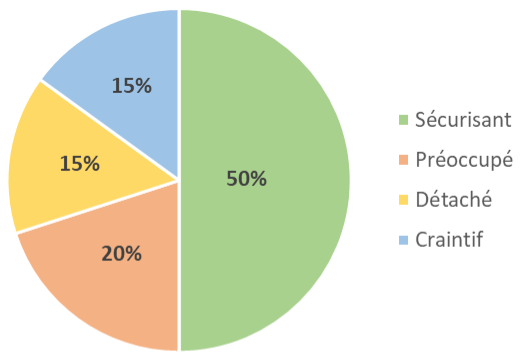

You may see yourself in only one of the dimensions of romantic attachment, in both, or none: know that all these options are possible and valid! Depending on where you are on the two axes, four possibilities emerge9:

(1) None of the dimensions suit you; this is the secure attachment style.

(2) Only the dimension of anxious attachment resonates with you; this is the preoccupied attachment style.

(3) Only the dimension of avoidant attachment speaks to you; this is the detached attachment style.

(4) Both dimensions are familiar to you; this is the fearful attachment style.

Here is a visual of the proportions in the general population9.

Concretely, how can this information benefit your intimate relationships?

Identifying your attachment style, recognizing what activates emotions and puts you in a vulnerable position in your relationships, allows you to better understand yourself and your partners and how you interact. Everyone benefits from learning more about romantic attachment as it relates to your relationship satisfaction and influences your sexual satisfaction.

Going back to the story of Alex and Evan, we can suppose that Alex has a preoccupied style while Evan has a detached style. Their needs and reactions are different, which can lead to more arguments, where each feels misunderstood. This dynamic does not mean that they are incompatible, but rather that their perspectives are different: one sees a 6 while the other sees a 9. It is not about knowing who is right, but rather about improving their understanding of each other's different points of view and sharing them more easily to their partners.

Here are some reflections that may help you:

- Identify your attachment style. Here is a free online questionnaire that gives you your result directly. You can also invite your partners to complete it and, why not, talk about it together afterwards.

- Recognize what makes you react, your own triggers. Try to better understand your reactions, emotions (e.g., anger, disappointment, sadness), and thoughts when interacting with your partners. In the story featured above, Alex felt disappointed that Evan did not consider him due to his lack of response. This disappointment manifested itself in anger towards Evan when he returned home. In turn, Evan felt irritated by Alex's reaction, which he did not understand and interpreted as being over the top. This refers to their difference in perception.

- Talk openly with your partners. If you and your partners talk about your attachment styles and the situations that activate you most emotionally, it can help your intimate relationships become more cohesive. By showing vulnerability, empathy, and curiosity about each other, you will be able to better understand one another during more difficult times. It is recommended that you have these discussions in a context where you feel calm and receptive, not during conflicts.

We hope that this article has given you some insights into how you and your partners function. If you feel the need, know that it is possible to work specifically on your attachment issues in therapy, both individually or with your partners.

*The use of the plural form for the term partner is intended to lighten the way this article is read and be inclusive of the various relational and sexual configurations of intimate relationships.

The publication of this article was made possible thanks to our partner, the Interdisciplinary Research Centre on Intimate Relationship Problems and Sexual Abuse (CRIPCAS), and the Fonds de recherche du Québec.

To cite this article: Bolduc, R., & Baumann, M. (2022, April 11). I see a 6 while my partner sees a 9, who is right? TRACE Blog. https://natachagodbout.com/en/blog/i-see-6-while-my-partner-sees-9-who-…

- 1Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Erlbaum.

- 2Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

- 3Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 2. Separation. Basic Books.

- 4Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 3. Loss. Basic Books.

- 5Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base. Basic Books.

- 6Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic Love Conceptualized as an Attachment Process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511-524.

- 7a7b7cBrennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-Report Measurement of Adult Attachment: An Integrative Overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment Theory and Close Relationships (pp. 46-76). Guilford Press.

- 8a8b8cMikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Press.

- 9a9bBrassard, A., & Lussier, Y. (2009). L’attachement dans les relations de couple : fonctions et enjeux cliniques. Psychologie Québec, 26(3), 24-26. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281390451_L'attachement_dans_les_relations_de_couples_Fonctions_et_enjeux_cliniques