Maël* is a 23-year-old bisexual non-binary person who went through a lot during their adolescence: rejection from their parents, periods of homelessness, sexual victimization, anxiety, addiction... They hit rock bottom but was able to access resources that helped them get back on their feet and thrive.

Maël's journey is not atypical: sexually and gender diverse individuals are twice as likely to be victims of physical or sexual violence as heterosexual and cisgender individuals1. Sexual and gender diverse youth between 15 and 24 years old are particularly at risk of experiencing violence, especially in a school environment.

Heterosexism and cissexism - sets of hostile and discriminatory attitudes and behaviors toward non-heterosexual people and trans or non-binary people2- leads to increased stress among sexual and gender diverse youth3. This stress, known as minority stress, in turn has negative physical, psychological and social repercussions4,5,6,7, for example:

- Low self-esteem;

- Symptoms of depression and anxiety;

- Suicidal thoughts;

- Poor school perseverance;

- Homelessness;

- Substance abuse.

In Maël's case, their coming out led to rejection by their parents and homelessness at 15 years old. Without financial support, Maël experienced a period of homelessness marked by anxiety and victimization, including sexual assault. After the assault, they used drugs as a lifeline to survive the suffering, which sank them further, exacerbating their anxiety and financial precariousness.

In this story, we can see that their parents' rejection placed Maël in a vulnerable situation. This led to multiple problems, which in turn had a negative impact on their psychological and social development.

What can help alleviate minority stress?

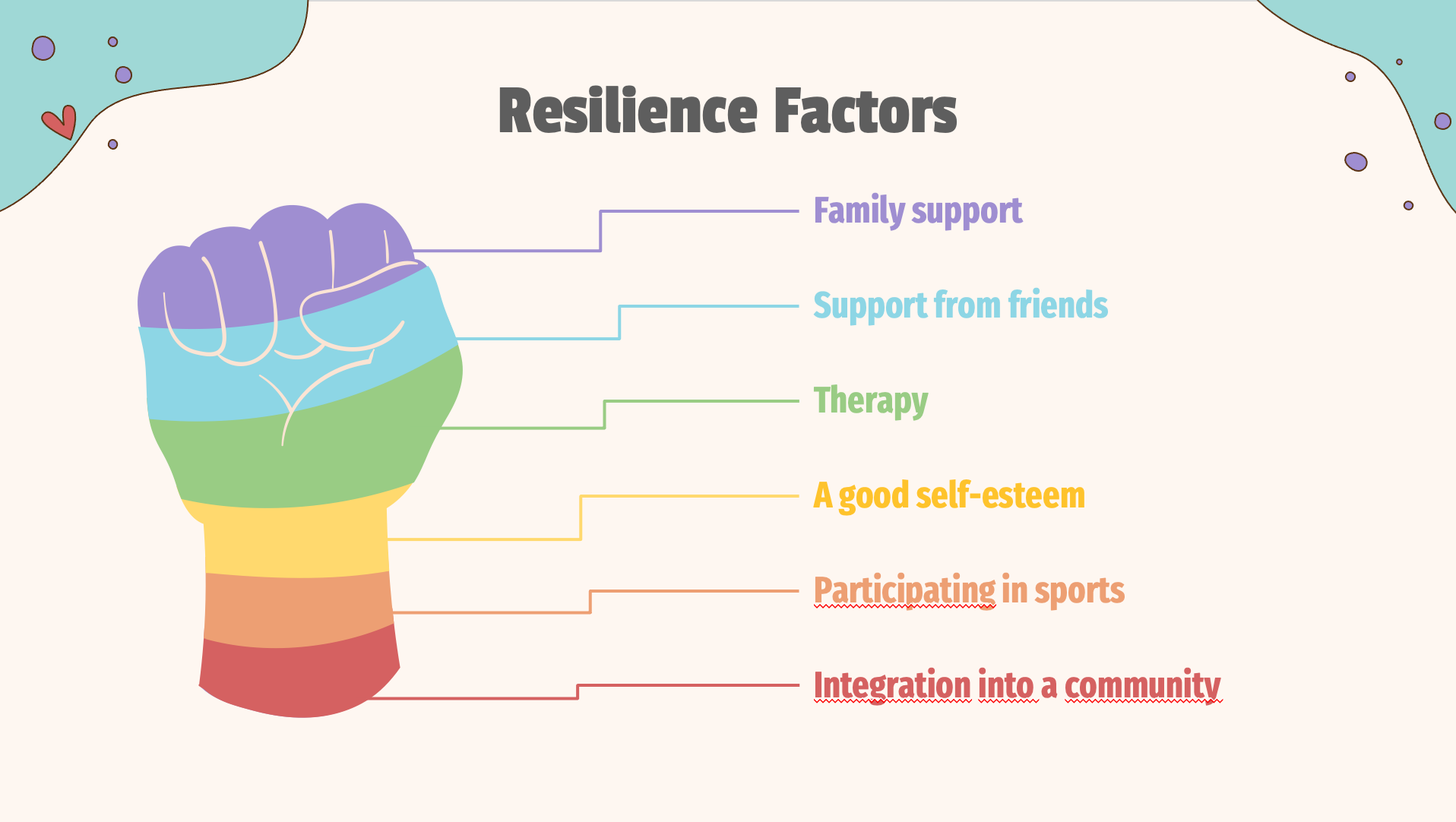

Fortunately, the stress experienced by minorities can be alleviated through individual strengths and access to social or community resources8. These strengths and resources promote resilience in sexually and gender diverse youth, enabling positive adaptation following experiences of victimization:

Family support is a key factor in the psychological adjustment of sexual and gender diverse youth9. Family therapy can help parents come to terms with their child's sexual orientation or gender identity, so that they can provide adequate support10.

Support from friends is associated with better physical and mental health11.

An affirmative approach to therapy is recommended when intervening with sexual and gender diverse youth, to promote their well-being12. This approach, which is based on respect for sexual and gender diversity, aims to support people in their identity exploration.

Good self-esteem promotes the psychological well-being of sexual and gender diverse youth13. Among other things, it reduces symptoms of depression14.

Participation in sports reduces the risk of substance abuse and the negative impact of minority stress on health11.

Integration into a community (spiritual/religious or cultural, online or made up of sexual and gender diverse individuals) can provide a sense of belonging that helps to offset experiences of rejection and discrimination9.

For example, in Maël's case, it was their participation in a support group for sexual and gender diverse youth, organized by Interligne, that made them feel less isolated. Then, therapeutic support offered by the CLSC helped them reduce their drug use and ease their anxiety. Maël then became a volunteer for Gris Montréal and now takes part in pride walks. This social engagement fosters their integration into the LGBTQIA2S+ community and boosts their self-esteem. Finally, they found a safe place at an inclusive gym to be physically active, Mouvement Infinity, whose mission is to provide a space for marginalized communities. Restoring their sense of security one step at a time, building on their strengths, and taking several actions to promote social integration are what enabled Maël to recover from their family's rejection.

A collective responsibility

Resilience can be developed from resources available to almost everyone. In this sense, it is "ordinary magic", not a superpower15. So, rather than thinking of resilience as a unicorn - rare and extraordinary - we should compare it to a squirrel, since it can be found everywhere16. Indeed, many young individuals of sexual and gender diversity, like Maël, manage to thrive despite a hostile environment17.

Everyone - especially parents, teachers, health professionals and therapists - can contribute to the resilience of sexual and gender diverse youth. It's essential to provide them with support and resources that promote their well-being. It's also important to remember that it's society's responsibility to fight heterosexism and cissexism upstream and protect LGBTQIA2S+ youth from the violence they are likely to experience daily. For example, action should be taken to ensure that certain environments (e.g., schools) are more open to sexual and gender diversity.

* The character of Maël in this article is inspired by a real person who agreed to share their story. The name and age of this individual have been changed.

The publication of this article was made possible thanks to our partner, the Interdisciplinary Research Centre on Intimate Relationship Problems and Sexual Abuse (CRIPCAS), and the Fonds de recherche du Québec.

- 1Jaffray, B. (2020). Les expériences de victimisation avec violence et de comportements sexuels non désirés vécues par les personnes gaies, lesbiennes, bisexuelles et d’une autre minorité sexuelle, et les personnes transgenres au Canada, 2018. Statistique Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2020001/article/00009-fra.htm

- 2Bastien Charlebois, J. (2011). Au-delà de la phobie de l’homo : quand le concept d’homophobie porte ombrage à la lutte contre l’hétérosexisme et l’hétéronormativité. Reflets, 17(1), 112-149. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005235ar

- 3Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000132

- 4Cénat, J. M., Blais, M., Hébert, M., Lavoie, F., & Guerrier, M. (2015). Correlates of bullying in Quebec high school students: The vulnerability of sexual-minority youth. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183(1), 315-321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.011

- 5Chamberland, L., Richard, G., & Bernier, M. (2013). Les violences homophobes et leurs impacts sur la persévérance scolaire des adolescents au Québec. Recherches & éducations, 8(8), 99-114. https://doi.org/10.4000/rechercheseducations.1567

- 6DeChants, J.P., Green, A.E., Price, M.N., & Davis, C.K. (2021). Homelessness and housing instability among LGBTQ youth. The Trevor Project. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/homelessness-and-housing-instability-among-lgbtq-youth-feb-2022/

- 7Goyette, M., & Flores-Aranda, J. (2015). Consommation de substances psychoactives et sexualité chez les jeunes : une vision globale de la sphère sexuelle. Drogues, santé et société, 14(1), 171-195. https://doi.org/10.7202/1035554ar

- 8Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000132

- 9a9bCeatha, N., Koay, A. C. C., Buggy, C., James, O., Tully, L., Bustillo, M., & Crowley, D. (2021). Protective factors for LGBTI+ youth wellbeing: A scoping review underpinned by recognition theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111682

- 10Harvey, R., Murphy, M.J., Bigner, J.J., & Wetchler, J.L (dir.). (2021). Handbook of LGBTQ-affirmative couple and family therapy (2e éd.). Routledge.

- 11a11bBlais, M., Bergeron, F.A., Duford, J., Boislard, M. A., & Hébert, M. (2015). Health outcomes of sexual-minority youth in Canada: An overview. Adolescência e Saúde, 12(3), 53-73.

- 12American Psychological Association. (2021). Guidelines for psychological practice with sexual minority persons. www.apa.org/about/policy/psychological-practice-sexual-minority-persons.pdf.

- 13Parmar, D. D., Tabler, J., Okumura, M. J., & Nagata, J. M. (2022). Investigating protective factors associated with mental health outcomes in sexual minority youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(3), 470-477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.004

- 14Hall, W. J. (2018). Psychosocial risk and protective factors for depression among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer youth: A systematic review. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(3), 263-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1317467

- 15Masten A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227

- 16Hamby, S. (2021, 2 mars). Trauma is everywhere, but so is resilience [vidéo]. TED Talks. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dTBqhQNUtrI

- 17Asakura, K. (2019). Extraordinary acts to “show up”: Conceptualizing resilience of LGBTQ youth. Youth & Society, 51(2), 268-285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X16671430