Often, we tend to pay more attention to behavioural manifestations rather than to their underlying causes. When interacting with youth displaying different behavioural difficulties, we may assign different labels to them, forgetting that they may have experienced interpersonal trauma (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, emotional abuse). Therefore, these labels can divert our attention from the suffering and wounds that may be hidden behind their behaviours. These beliefs substantially influence our responses and interventions towards youth: adults may feel that they need to "break" the youth's behaviour, which can unfortunately lead to power struggles, leading youth to become defensive rather than feel seen and heard.

Certainly, the behaviours of youth who have experienced interpersonal trauma can sometimes be difficult to understand, and can generate feelings of helplessness, confusion, hopelessness, anger, or even shame in the adults (e.g., parents, foster parents, teachers, caregivers) who care for them. To regain a sense of hope about the behaviours that some youth who have experienced trauma may exhibit and about your ability to offer them a response that will promote healing of their traumatic wounds, I invite you to put on your detective hat and get out your magnifying glass to take a closer look at what may be hidden beneath their behaviours. This will allow you to adopt a position of discovery of their inner world and enable you to intervene in a sensitive manner adapted to their needs.

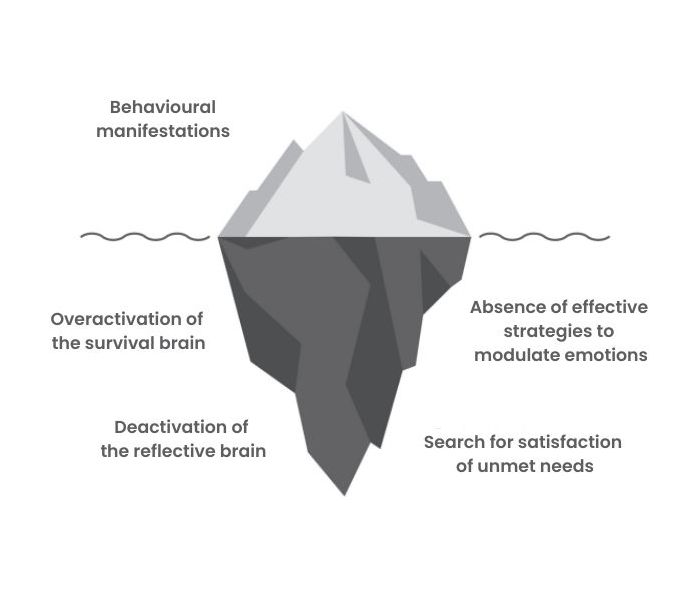

The iceberg model

In my book « 10 questions sur le trauma complexe chez l’enfant et l’adolescent : Mieux comprendre pour mieux intervenir » (10 questions on complex trauma in children and adolescents: Better understand to better intervene) (Éditions Midi trente), I propose the "iceberg model" to help you better understand the behaviours of traumatized youth. This model illustrates what may be "underneath" the behaviours of youth.

The iceberg model reminds us that the behaviours and emotions of youth who have experienced trauma can be explained by:

1) the overactivation of their survival brain;

2) the deactivation of their reflective brain;

3) the absence of effective strategies to modulate their emotions;

4) the search for the satisfaction of unmet needs.

Let's go through the reasons that may underlie the behavioural and emotional manifestations of youth who have experienced trauma one by one.

1. The overactivation of the survival brain

The survival brain is the part of our brain that is activated when faced with a danger or threat. To protect ourselves, our survival brain triggers different types of reactions in our body, such as fight, flight, freeze, or fawn.

Young people who have experienced chronic and repeated interpersonal trauma have had their survival brains activated multiple times in their lives. Consequences can result from activation of the survival brain too often or for too long. For example, the brain may have difficulty differentiating between a real danger and a harmless situation, so it may misfire and trigger fight, flight, freeze or fawn responses in situations where there is no real threat.

In addition, the survival brain of traumatized youth may remain "on" even in the absence of danger, thus, becoming the default mode of functioning. Subsequently, youth may be hypervigilant, meaning they are constantly on guard and alert. On the other hand, some youths' survival brains may eventually run out of steam because they are in a perpetual state of mobilization: they may no longer be effective, and they may appear to be unaware of danger and their environment, amorphous and passive.

2. The deactivation of the reflective brain

The reflective brain is the head of executive functions, operated by our prefrontal cortex. In concrete terms, executive functions allow us to analyze, plan, organize, regulate our emotions and behaviours, evaluate solutions, delay, or inhibit a response, anticipate consequences, think of alternatives, solve problems, remember and execute instructions, etc.

When our survival brain is activated, our reflective thinking brain shuts down, because when we are faced with danger, it is better to act than to think. Due to the possible overactivation of the survival brain of young people who have experienced trauma, their reflective brain may often be turned off which may impact the development of the functions associated with it. These functions are essential to successfully navigate their environment (whether at school, at work, or in society in general).

Difficulties with executive functions, which allow us to control our thoughts, emotions, and actions, can then be observed. For example, this can result in:

- A low tolerance for delays;

- Difficulty remembering and carrying out instructions, making decisions and choices, considering others’ point of view, solving problems and seeking solutions, analyzing, planning and organizing;

- Staying fixed on an idea;

- Inattention and impulsivity.

3. The absence of effective strategies to modulate their emotions

The lack of effective strategies in this area may lead youth to rely on a variety of behaviours to temporarily reduce distress and internal tension (e.g., self-harm, regressive behaviours, thrill-seeking, substance use, risky sexual behaviours, eating disorders).

This lack of strategies may be related to a variety of factors: lack of external support to regulate emotions, lack of adults as healthy models of emotional regulation, lack of access to the reflective brain, underdeveloped emotional language that promotes misunderstanding of internal experience, emotions whose intensity, nature or frequency exceed the youth's resources, etc. In short, youth who have experienced trauma have not always had the opportunity to rely on adults to help them regulate themselves, which may have hindered the development of their emotional regulation skills.

4. The search for the satisfaction of unmet needs

Traumatized youth have often experienced neglect, unpredictability, or inconsistency in having their needs met. As a result, they may have learned to meet their needs in other ways or to act out for their needs to be heard and met. Certain behaviours, such as crying, screaming, throwing a tantrum, hoarding food, stealing things, lying, making up stories, inventing qualities or skills, exhibiting inappropriate sexualized behaviours, attempting to control others or the environment, violating others' boundaries, may be a way for these youth to satisfy their needs that are unmet.

These needs may be:

- Physiological (e.g., eating, drinking, sleeping);

- Relational (e.g., belonging, friendship, intimacy);

- Emotional (e.g., validation or expression of emotions);

- Safety needs (e.g., physical/psychological/material safety);

- Esteem needs (e.g., recognition, self-awareness, identity development);

- Achievement needs (e.g., experiencing successes), etc.

Conclusion

Humans are complex and behaviours can have multiple sources. The idea here is simply to start thinking about what might explain the behaviours of children and adolescents who have experienced trauma. This then leads us to think about what we can do to help them "calm down" their survival brain, "build" their reflective brain, modulate and regulate their emotions, and meet their needs.

One thing to remember is that the behaviours seen in traumatized youth are often just the tip of an iceberg. My advice? Don't be afraid to get wet and dive under the water to find out what's underneath the tip of the iceberg and why youth behave the way they do. By targeting the underlying causes of behaviours rather than the apparent symptoms, your interventions will be more effective, and the maladaptive behaviours youth may exhibit will be more easily extinguished. In addition, youth will feel that they can finally trust adults to support them and meet their needs, and the relationship between you will be a critically important healing opportunity.